Whom Do Voters Actually Blame for Inflation?

They see several causes at work—including some out of Biden’s control.

By Nyron Crawford and Alexandra Guisinger

November 21, 2023

Inflation is still very much on the minds of voters and politicians.

A recent poll by the New York Times/Sienna College shows Biden trailing Trump in key battleground states, and many analysts point to Americans’ concerns about inflation as a continued source of discontent. During the RNC’s third presidential primary debate, candidates highlighted how inflation is burdening—or to use Chris Christie’s term, “choking”—American households.

The performance of the U.S. economy has historically been an important factor in presidential elections. By important objective indicators such as growth and employment, the economy is healthy and recovering faster than similar economies. But partisan polarization injects politics into subjective perceptions of how the economy is doing.

How are voters thinking about inflation—and whom do they blame? Here’s what the data say.

The Economy Is Doing Better, but Voters Don’t See It That Way

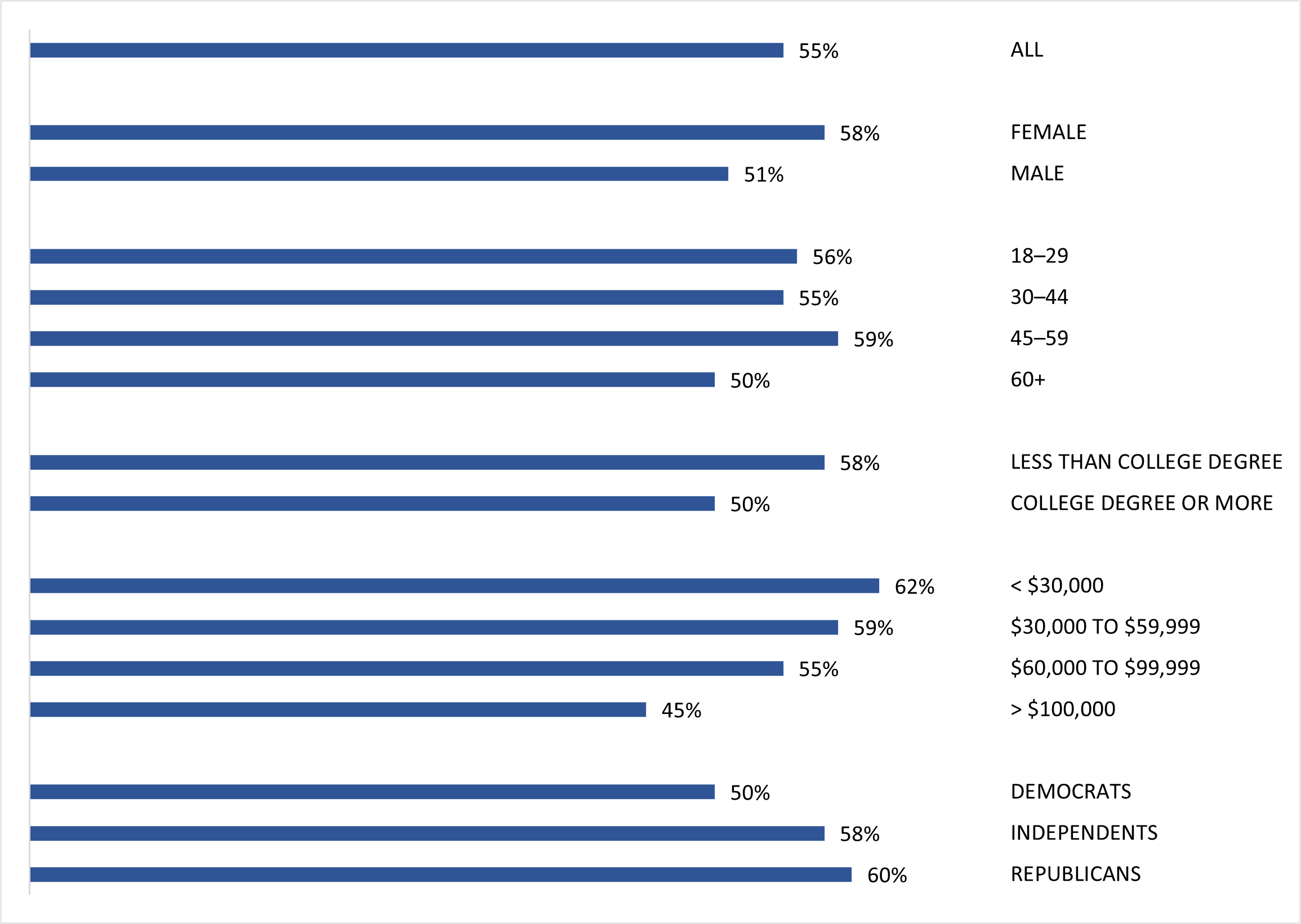

Despite falling inflation and the Inflation Reduction Act lowering medical and energy costs, Americans continue to believe that the economy is “getting worse.” In a June survey fielded by NORC for the Foreign Policy in a Diverse Society Project, a majority (55%) of the more than 3,000 respondents reported feeling the impact of inflation “a lot” in their own lives. The figure below shows that this feeling is present among Americans of different genders, age groups, and income and education levels—as well as among Democrats and Republicans alike.

Figure 1: Inflation has dramatically affected the lives of most Americans

% saying inflation has affected their life “a lot”

Whom Do Voters Blame?

Although it’s been easy for many voters to see and feel the recent spike in inflation, it’s been much harder to explain it. Some economists point to monetary policy in the last year of Trump’s administration, others to lowered unemployment, energy prices, and supply-chain issues, and yet others to rising corporate profits or consumer demand.

This muddled story is reflected in how politicians talk about it. In the last GOP presidential primary debate, candidates were quick to blame inflation on President Biden. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis pledged “to take all the executive orders, the regulations, everything involving Bidenomics, … rip it up and … throw it in the trashcan on day one where it belongs.”

At the same time, some candidates' solutions highlighted factors outside of Biden’s direct control. DeSantis first blamed Congress and both parties for inflation before calling for reining in the Federal Reserve Bank. Vivek Ramaswamy and Tim Scott pushed for greater domestic production—ironically, a major aim of Biden’s policies.

Given the debate among elites, it’s not surprising that the public is itself uncertain about the causes of inflation. In this June survey, only 14% said that they understood the causes of today’s inflation “very well.”

The survey provided a list of common explanations for today’s inflation and asked respondents “How much, if at all, do you blame each of the following for inflation?” The figure below shows the percentage of people who blamed each factor “a lot.”

Figure 2: Americans blame recent inflation on many things

% of Democrats, Republicans, Independents, and all Americans saying that they blame each factor “a lot”

The five most-cited causes were: large corporations (63%), the COVID-19 pandemic (57%), federal government spending (53%), the supply chain (53%), and the price of foreign oil (53%). In contrast, consumer behavior and wage demands—frequent targets of politicians both in the U.S. and abroad—received less blame.

How Partisanship Does (and Doesn’t) Matter

Prior scholarship on the public’s economic perceptions and their attribution of responsibility for the economy suggests that partisanship influences both. Individuals identifying with the party out of office—Republicans, in this case—will typically perceive greater harm and attribute that harm to the incumbent party, while individuals identifying with the party in office will do the opposite.

The first figure showed that Republicans and Democrats differed modestly in how much of an impact inflation has had in their daily life. The second figure shows that they differed much more about whom to blame. Almost 80% of Republicans blamed government spending a lot compared to less than 40% of Democrats. In contrast, Democrats were far more likely (75%) than Republicans (54%) to blame corporations. Both Democrats and Republicans were much more likely to blame the other party than their own party.

In other cases, Republicans and Democrats’ opinions looked more similar, even regarding issues that are becoming increasingly polarized, such as the war in Ukraine. Last year, Biden blamed inflation on Putin and Republicans pushed back. Among the public, however, about a third identified the war as a major cause of inflation, with little difference between Republicans and Democrats. Similarly, voters from both parties see the price of foreign oil as a major cause of inflation.

What do we make of all this? Incumbent politicians—including conservative leaders like Rishi Sunak of the United Kingdom—tend to blame inflation on external forces, like the war in Ukraine, supply chain backlogs, wage demands, and consumer behavior. Those from the other party who want to win the next election naturally blame the current government’s policies.

But voters seem to have a relatively nuanced picture of what causes inflation. To be sure, they do tend to blame the other party. But they believe that many factors, some outside the government’s control, drove the recent spike in inflation.

This FPDS report was additionally published on the Good Authority website.

Nyron N. Crawford is associate professor of political science and faculty fellow in the Public Policy Lab at Temple University. He is the author of the forthcoming Marked Men: Black Politicians and the Racialization of Scandal (New York University Press, May 2024).

Alexandra Guisinger is associate professor of political science at Temple University. She is co-principal investigator of the Foreign Policy in a Diverse Society project, housed in Temple University’s Public Policy Lab. She is the author of American Opinion on Trade: Preferences without Politics (Oxford University Press, 2017).

This research was undertaken as part of the Foreign Policy in a Diverse Society project (DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/QJR49), which is supported by funding from Carnegie Corporation of New York.